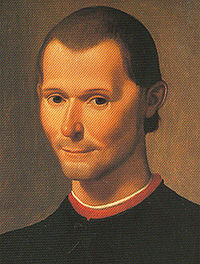

I heard quite a lot–references and allusions–about Machiavelli during my early teen years, and that lead me to get around to reading The Prince at some point during my time living in Switzerland–I was 16 at the time.

I heard quite a lot–references and allusions–about Machiavelli during my early teen years, and that lead me to get around to reading The Prince at some point during my time living in Switzerland–I was 16 at the time.

I remember being impressed and amused by the book, and by what I knew about how it connected to political life in Italy at the time.

Other than the occasional quotation, I haven’t revisited The Prince since then.

But now I may have to.

I’ve just spent some time reading a piece from 1958 by Garrett Mattingly wherein he makes the case that The Prince, rather than being taken at face value as a “scientific manual for tyrants” was actually intended as a political satire in the Swiftian mode. How has this been part of the critical discussion for more than 50 years, and this is the first I’ve heard of it? Again my information-gathering network must not be as good as I think it is.

If you’re even vaguely interested in Machiavelli, or this historical context of The Prince, I’d recommend reading Mattingly’s piece. Here’s a tiny bit of it:

Moreover, The Prince is easily Machiavelli’s best prose. Its sentences are crisp and pointed, free from the parenthetical explanations and qualifying clauses that punctuate and clog his other political writings. Its prose combines verve and bite with a glittering, deadly polish, like the swordplay of a champion fencer. It uses apt, suggestive images, symbols packed with overtones. For instance: A prince should behave sometimes like a beast, and among beasts he should combine the traits of the lion and the fox. It is studded with epigrams like “A man will forget the death of his father sooner than the loss of his patrimony,” epigrams which all seem to come out of some sort of philosophical Grand Guignol and, like the savage ironies of Swift’s Modest Proposal, are rendered the more spine chilling by the matter-of-fact tone in which they are uttered. And this is where the paradox comes in. Although the method and most of the assumptions of The Prince are so much of a piece with Machiavelli’s thought that the book could not have been written by anyone else, yet in certain important respects, including some of the most shocking of the epigrams, The Prince contradicts everything else Machiavelli ever wrote and everything we know about his life….

Me… I’m going to have to go reread The Prince now with this in mind. It’s a short read, so it’s hardly onerous, and of course even as far from my library as I am today, reading the book won’t be a problem.

2 comments for “Now I’m Going To Have To Reread The Prince”